| brucekluger.com |

Time.com, November 13, 2003 What Gene Robinson Can Learn From Jackie Robinson The new Episcopal bishop is successfully taking a low-key approach to his detractors, notes Bruce Kluger — just like the legendary Dodgers infielder. By Bruce Kluger With the Episcopal Church in a perilous state of fracture, one would expect that V. Gene Robinson— whose consecration as the first ever openly homosexual Anglican bishop instigated the rupture—would use this landmark event to strengthen the public case for gay rights, both in and out of the church. This has not been the case. Indeed, since his appointment, Bishop Robinson has responded to the condemnation of thousands of fellow parishioners—including that of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, himself—not with proud chest-thumping or a passionate polemic on the need for tolerance, but instead with empathy, even support, for his adversaries. “There are faithful, wonderful Christian people for whom this is a moment of great pain and confusion and anger,” Robinson said. “If they must leave [the church], they will always be welcomed back.’” Why the humble self-control? Wouldn’t it better serve Robinson—and the church itself—to celebrate his consecration with a flashy, public victory lap, if not the sweet retribution of a pointed “I told you so?” Not necessarily. In fact, Robinson’s silence may be his smartest move yet. Half a century ago, a similar strategy was employed—with remarkable success—by a man who coincidentally shares the Bishop’s surname: Jackie Robinson. When Jackie Robinson first took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, he did so having made a promise to the team’s president, Branch Rickey. Two years earlier, Rickey had met with Robinson, then a star in the Negro Leagues, grilling him for three hours over whether he could endure the personal pain of being the first black man to play Major League Baseball. A devout Christian, Rickey wanted to test Robinson’s ability to—as they say in the Bible—turn the other cheek. Replicating the ugly bigotry of the time, Rickey shouted at Robinson, hurling at him a litany of venomous epithets and racial slurs. Ultimately, Robinson withstood the mock attack, and vowed to Rickey that, were he to be invited to join the club, he’d remain silent for three years, no matter how vitriolic the personal and professional assaults. True to his word, Robinson kept his feelings to himself, and went on to become a star, in the end using his bat and base-running wizardry to silence those unable to see past the color of his skin. Only after the three-year promise had elapsed would Robinson begin to talk back. But by then he’d already achieved his and Rickey’s mission: the American Pastime was well on its way to becoming desegregated. Like baseball’s Robinson, the church’s Robinson arrives in the major leagues with glowing stats. Over the years, he has launched and sustained countless programs geared at educating and enlightening congregants of all ages; his ecumenical and interfaith resume has taken him to the cradle of his faith—the Middle East—where he has worked tirelessly with Christians, Jews and Muslims alike; and his unflagging community outreach efforts have tackled a host of social ills, from unaffordable housing to inadequate health care to the scourge of HIV/AIDS. These are the accomplishments that brought Bishop Robinson to the international stage—not his sexual orientation—and it would be a shame if he or his newly expanded parish allowed those works of humanity to be upstaged by the antics of a mob of angry bleacher bums. Like the integration of baseball, organized religion’s centuries-long practice of discrimination—of women, of gays—will come to an end in our lifetime. Those in Bishop Robinson’s corner know this to be true, as do those who oppose him. It’s now simply a matter of waiting for the storm to pass. That’s why it’s okay for Gene Robinson to resist the temptation of facing off with his enemies, and, instead, letting them fight it out among themselves as he quietly goes about his work. Just as the Brooklyn Dodgers’ number 42 achieved the greater objective of integrating baseball through the smaller but significant acts of sharpening his lead off first and perfecting his swing, let us hope that Bishop Robinson will remain unbowed by the heckling from the pews, and continue to grace the world pulpit as a shining example of decency and goodness. |

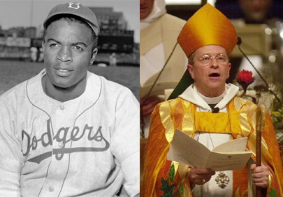

The baseballer and the bishop: Jackie and Gene Robinson.