| brucekluger.com |

NickJr.com, March 2000 In the Trenches With Bruce Kluger Daddy's Bill of Rights By Bruce Kluger True story: I am from Baltimore, and like most locals there, I was raised an Orioles fan; my wife is from Cleveland, and, likewise, an Indians disciple. While fiercely protective of our hometown turfs with one another, neither of us realized how much we’d been foisting our baseball biases on our daughter, Bridgette. Then one afternoon—Bridgey was about two-and-a-half—I was trying to get her to take a nap, and found myself trotting out a favorite bribe. “Please try to sleep, honey,” I implored her, “and if you do, I’ll make you a promise: when you wake up we’ll go out for Indian food.” “No, no,” Bridgette complained, “not Indian food. Oriole food!” As proud as I was of her at that moment (clearly she had made the right choice), I instantly recognized that Alene and I had somehow failed our little one. While as parents we’d managed to stay on the same page with respect to more basic matters (bedtime, TV privileges, manners) we’d obviously confused our daughter about life’s more burning issues—like baseball. Why were the Indians and Orioles even sharing the same part of Bridgette’s brain? I asked myself. After all, a true-blue Baltimore descendant shouldn’t even know other teams exist before the age of nine—especially the Indians. And, more to the point, which parent should pick the child’s favorite baseball team in the first pace? The answer came back to me faster than a three-year-old’s meltdown at dinnertime: Daddy. Now before you jump out of your skin and call me a sexist, hear me out. Anyone who knows me will tell you I’m a passionate, equal-opportunity father. With the exception of pregnancy and breast-feeding, I am convinced that men and women can—and should—share the joys and hardships of parenting evenly, with Mom and Dad functioning interchangeably at the top of the food chain, whatever the task at hand. But as Bridgette moves into the fives, and Audrey begins to walk, I am discovering that, even as my identity nicely reshapes itself around the concept of fatherhood, I'm losing touch with many of those things that make a Daddy a Daddy in the first place. In other words, in my efforts to be an equal co-parent, I think I’m in danger of throwing my inner-baby boy out with the bathwater. Why, for example, when I enter the grocery store, does the pretty cashier look at me and say “Baby sitting today?” as opposed to “Hey, good lookin’” Why have my brothers stopped calling me to talk about how our alma mater’s basketball team blew it again in overtime, and instead just ask me if I have any new pictures of my daughters to send them? Why do I know more about Pokemon than Pam Anderson? So maybe the Indians-Orioles incident was no fluke. Maybe it was a secret message from “the boys of summer,” calling out to me to rediscover my masculine roots. Either way, I knew I owed it to my daughters—and to fathers everywhere—not only to seize the privilege of being a major league parent, but along with it, a half-dozen other inalienable rights that separate the Pops from the Moms. Herewith, my Daddy's Bill of Rights: The right to pick our children’s favorite baseball team, until such time as the child is old enough to make his or her own choice (but not before the age of seven). The only exception to this rule is if the father is a Boston Red Sox fan, in which case the child should be exposed to the team in small, careful doses, all the while being braced for the inevitable heartbreak that goes with rooting for Beantown. To wit: the child should be told as early as age five that the Red Sox will never—ever—win a World Series in her lifetime. Naturally, the child is permitted to root for Mom’s team, too. But only when Dad’s team isn’t playing, or is in the middle of rain-delay. The right to give them any designated nickname we want. My buddy calls his son Zachary “Zach the Maniac”; my brother uses “Skittles” to beckon his two-year- old, Emily. Me, I've addressed Bridgette as “Chopstick” for four-and-a-half years, and just started calling Audrey “Chewy” and “Pooh” (I can’t choose between the two—both work so well). It begins, I suppose, in summer camp, when boys are hell-bent on giving one another nicknames, most of them unflattering monikers that allude to hair color, weight or flatulence. Just consider this the grown-up version, in which the chosen pet names run the gamut from the endearing (“Cuddles”) to the suggestive (” Stinky”). And, by the way, for any of this to work effectively, you need to call the child by his proper some of the time. Otherwise, the kid will never know when he’s being called on in school. The right to put funny things on their heads. It must be a chemical component hidden within in the Three Stooges chromosome (the little-known genetic strand that allows men, and only men, to find Larry, Moe and Curly a riot); but placing an object on baby’s head is simply entertaining to us. Besides, if it wasn’t meant to be done, God wouldn’t have made children’s heads so big and given us cameras. As I write this, I can’t tell you exactly why I felt compelled to pose Bridgette, at four weeks, with a bottle of aspirin perched on her still bald pate, or why at six months, Audrey needed to wear a Play-doh-and-celery chapeau. All I can tell you is that the pictures are now classics. And if it means anything, all my guy friends find them hysterical. The right to continue to lose their socks. Hey, we’d lose our own socks if our shoes weren’t holding them on. The right to feed them crap. I have never been what you’d call a gourmet. I loved cafeteria food as a school kid, ate from vending machines in college, and to this day still believe the three basic food groups are Gum, Chips and Twinkies. Consequently, as long as my wife is at the wheel in the nutrition department (and, thankfully, she is as devoted to the food pyramid as I am to Pez), I get dibs on handing out the goodies in my household—from desserts to treats to the occasional smuggled Peppermint Patty before bedtime. I know this unfairly makes me a more popular fellow with my girls than my wife—and but, hey, that’s the way it is. Pain of motherhood and all. The right to show them scary movie clips. I once flew from Prague to New York with Bridgette, during which the in-flight movie was Men in Black. No manner of pleading with her to turn her head worked for me—she was mesmerized by the film (especially the scene in which a woman delivers a baby octopus-alien in the back seat of a car). Since that day, and with the help of an extensive video library, I’ve become hooked on watching my daughter try to wrap her little mind around moviedom’s wilder special effects. She’s infinitely more engaging—and engaged— than when she watches, say, Cinderella for the ninetieth time, and I love being witness to it. Would I let her see The Exorcist? Of course not. Would I show her Beetlejuice? In a heartbeat. By the way, as for nightmares, the only film that’s caused Bridgette to awaken, crying, in the wee morning hours was Jurassic Park II: The Lost World. Turns out she saw it on a play date at a boy’s house. Naturally, I would never have let her watch that film. Not when Part I was so much better. The right to our own phraseology. When Alene crosses the street with Bridgette, she gently warns her, “Remember to hold Mommy’s hand, and always look both ways.” When I’m the crossing guard, my admonition is a bit more colorful. “Don’t let go of my hand, Bridgey, because if a bus runs over you, it’s all over. You’ ll be squashed like a bug.” From birth, I suppose, children’s minds are programmed to take in the vital information, then discard the extraneous, unessential and otherwise goofy. Bridgette doesn’t bat an eyelash when I push the envelope with the overly graphic or daringly off-color. In fact, she finds me harmlessly amusing. Like mother, like daughter. The right to love them like a man. Guys punch each other for fun, hug too hard, and say things like, “Get your butt over here, dummy.” And that’s when they like each other. I don’t mind this—it’s just testosterone doing its thing. Being a boy in a girls’ world (and, by the way, if you haven’t figured out it’s a girls’ world, I would advise you not to have daughters) is a delightful burden, one in which we constantly seek ways to adapt to the natural, biological and God-given wisdom of women. As fathers, we listen carefully to the way mothers parent, then make the ideas our own. In other words: I love the hell out of my girls. And anybody tells you different, I’ll deck ‘em. |

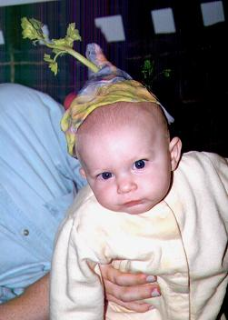

Head games: Audrey, with Play-doh-and-celery hat.