| brucekluger.com |

DadMag.com, July 2001

How much does a child really understand the complicated issue of race? By Bruce Kluger Sometimes your kids make you proud; other times it gets a little complicated. My older daughter's babysitter, Bonny, recently told me an unsettling story. She was walking Bridgette home from school, when Bridgey, who is five, eyeballed a billboard featuring a giant photo of a glowering, bare- chested black model. Staring at it for a long while, Bridgette suddenly announced, quite matter-of-factly, “That man is scary. I don’t like black people, except for you, Uncle Guy and Evlyn.” (Uncle Guy is her godfather, Evlyn is Bonny’s cousin, who also babysits for my daughters.) Astounded—but ever collected—Bonny said to Bridgette: “That’s not very nice. What if I told you I didn’t like any pink people except for you and your baby sister? How would you feel about that?” Bridgette was livid. “That’s mean,” she shot back—then sank into a stony pout. Bonny says the two of them didn’t speak to one another for four blocks, until, just before they arrived at home, Bridgette offered up a quiet apology to her—several times—telling her she didn’t really mean what she had said. When Bonny related the story to me the next day I was, to say the least, floored. Ours is not a household that practices racism. In fact, it is a source of pride to both my wife and myself that, with the help of a few splendidly written children’s books, Bridgey already understands the shame of slavery and the heroics of Martin Luther King, Jr. Not bad for five. So what compelled her to make this alarmingly disparaging comment? My first guess was that she was simply parroting a school chum. (I find that classmates always make the best scapegoats for my own kids’ behavioral problems.) But when I ran the story by Kathleen, the director of Bridgette’s pre-school, she simply smiled. “Your daughter’s right on schedule,” she said. “During the fours and fives, children begin noticing differences and making choices about those differences—almost arbitrarily. It can be anything from hating peas to liking boys. Skin color is just another one of those selections. It’s a way of verbalizing their individualism.” Okay. The part about being right on schedule made me feel somewhat better; good to know that my little Archie Bunker has company. But the other part I’m not so sure about. Why on earth should I take comfort in knowing that Bridgette’s inchoate (albeit innocent) prejudice is part of the natural development of her identity? Am I expected to stand by and proudly watch as that personality quirk blossoms into a full-throttled bigotry? The answer to all of the above, of course, is: relax. Indeed, Bridgette’s announcement of her preference for white people is only as dramatic as the listener permits it to be. Had Bridgette informed me that, say, her occasional pre-school paramour, Lucas, had acted like a silly cheesehead to her, and that she was officially writing off boys altogether, would I have even batted an eye? Not likely, especially knowing that such an embargo would be lifted the moment Lucas was nice to her again. So why did her comments about skin color land with such a thud for the adults in her life? Primarily because we bring so much painful knowledge to the subject. Not so with Bridgette, who, bless her soul, doesn’t view racism in the same powder-keg way grown-ups do. To her or any five-year-old, preference of skin color is as mercurial and transient and idiosyncratic as preference of blouse color (which any parent of a girl can tell you varies by the minute). Even with her relatively advanced knowledge of civil rights history, Bridgette doesn’t equate the larger injustices of social prejudice—which she truly understands from her storybooks to be wrong— with her very personal, very fleeting selection of white over black. And, of course, it was fleeting. Only a few days after her encounter with Bonny, Bridgette was back in her weekly dance class (in which she is the only white child), cavorting with her fellow ballerinas as playfully as ever. I am now convinced that, had I stopped her mid-plié and reminded her about her alleged predilection for white folks, she wouldn’t have had the foggiest idea of what I was talking about. Which is not to say we shouldn’t monitor the way our children view the genuine social inequalities that surround them, and help them arrive at healthy solutions when conflicts arise. In Bridgette’s case, my wife was encouraged—impressed, even—that she had used a four-block sulk to work the problem out in her own mind, arriving at the conclusion that she’d said something hurtful to Bonny and needed to apologize to her. Therefore, my wife said, we could drop the issue safely. As always, I was a little more apprehensive and took an extra step, stopping by the bookstore and walking out with a perfectly wonderful tale called Sister Anne’s Hands (written by Marybeth Lorbiecki, illustrated by K. Wendy Popp), all about a black nun who confronts—and overcomes—racism in an all-white school. Bridgette loved the book and, more importantly, seemed to understand it. If, as a parent, I could change one thing about the way I responded to this little ripple in my daughter’s development, I think I would have preferred not to have been swept into such inner turmoil about it at the outset, and instead trusted my child to be the kind little girl I know she is. After all, good parenting requires faith and patience and love—qualities which, not incidentally, always transcend color. |

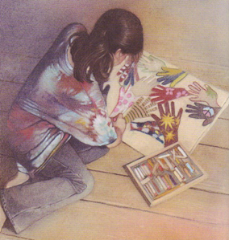

Illustration from the book Sister Anne's Hands."